The Other Mineral Powers

A brief review of critical minerals in Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, and Argentina

Much of the global conversation on critical minerals today centers on a limited group of dominant players. China’s overwhelming grip on refining and processing, the scale of Australia’s lithium exports, the strategic cobalt dependence on the Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia’s nickel-led industrial policy, and U.S. reshoring efforts under the Inflation Reduction Act form the core of most policy, market, and media narratives.

There is a set of emerging countries whose mineral endowments, institutional reforms, or geopolitical alignments make them candidates to play consequential roles in the energy transition even if they are not yet central to production volumes or supply chain flows. These countries often operate in a state of internal challenges in their mineral or mining sector such as being legally open but operationally fragmented, rich in resources but short on logistics and infrastructure, eager for investment but impacted by institutional legacies that undermine market stability.

In the context of the energy transition, these contradictions matter. Energy technologies like batteries, transmission infrastructure, solar panels, wind turbines, electric motors, etc. are mineral-intensive in ways that differ from the fossil fuels value chain. As demand for copper, lithium, rare earth metals, and nickel outpaces traditional supply channels, secondary and underleveraged producers will become increasingly important to fill structural gaps and reduce the risk of relying on a single country for the global supply of a single metal.

In this piece I focus on three such countries: Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, and Argentina. Each of these represents a different model of emergence. Argentina offers legal clarity and geological wealth but issues like macroeconomic fragility and fragmented governance introduce challenge. Kazakhstan has overhauled its mining laws and institutional architecture but remains dominated by state-owned entities and an outdated energy base. The most interesting case is Afghanistan (I have always been interested in Afghanistan!) Despite decades of what might be interpreted by some as external support, and great potential in copper, lithium, and rare earths, unfortunately the country remains a case study of institutional collapse and geopolitical exclusion. I did a similar post earlier on Ukraine, right after its minerals agreement with the United States. This post extends that analysis, focusing on less visible but strategically relevant mineral provinces whose future roles may be of geopolitical importance.

The cases of Afghanistan Argentina, Kazakhstan, and reveal that the global race for mineral access would extend to a series of less visible countries in the near future. Each of these countries, in its own way, is being pulled into the gravitational field of competing geopolitical and commercial agendas. I’ve also added summarized SWOT style tables at the end of the post for each country’s minerals landscape.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan's mineral endowment is exceptional. Geological surveys by the USGS and the Afghan Geological Survey (AGS) identify deposits of copper, iron, lithium, rare earth elements (REEs), barite, gold, and chromite, collectively valued at over $1 trillion. These resource estimates mean that Afghanistan has the potential to become a supplier of high-demand materials for the global energy systems. This includes copper for grid expansion, lithium and REEs for electric vehicles and energy storage, and barite for geothermal and hydrogen systems.

But sadly, this promise exists almost entirely on paper. Despite a 2018 Minerals Law aligned with international standards, a digitized Mining Cadastre Administration System (MCAS), and targeted reforms by the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum (MoMP), no large-scale mineral project has reached sustained development. Instead, Afghanistan's extractive sector is defined by institutional collapse, elite interference, informal mining dominance, and a near-total absence of downstream or infrastructure-linked planning. Attempts to build a modern mining regime, technically supported by over $960 million in donor funding, have yielded minimal results.

On paper, Afghanistan’s 2018 legal framework provided for open licensing, revenue-sharing with provinces, environmental and social impact assessment requirements, and transparency in beneficial ownership, but nearly all of these features were undermined in practice. The High Economic Council (HEC) which is an extra-legal executive body, routinely overrode technical decisions, while legal loopholes allowed politically connected individuals to hold mining licenses through relatives or proxies.

This pattern of elite capture extended into Parliament, where as many as 60% of members were reported to have direct interests in mineral assets, resulting in deliberate immobilization of the reform process. Afghanistan withdrew from the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in 2019 and shelved its own commitments to regular contract publication and independent oversight.

Institutionally, the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum was hollowed out. Staff turnover, political interference, and the collapse of donor support after 2021 events left MoMP and AGS with little technical capacity and even less operational reach. Many sites identified for strategic resource development were physically inaccessible due to insecurity or contested control. Even where licenses were issued, the state had no ability to inspect, monitor, or enforce compliance.

Although Afghanistan's mineral base aligns perfectly with global energy transition needs, its policy and infrastructure frameworks have failed to make the connection. Lithium deposits in Nuristan, REEs in Helmand, and large-scale copper in Logar have all attracted international attention but none of these resources are backed by sufficient energy infrastructure to process them domestically. The fact that the country has no direct access to international waters create additional complexities to market access or export routes because any meaningful long-term infrastructure planning should consider Iran or Pakistan’s blessing.

The energy nexus for the mineral sector is another challenge as the national grid is underdeveloped and fragmented, importing up to 4,500 MW from Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. Power reliability is low, and most mineral-rich provinces lack dedicated transmission lines. A proposed linkage between mining, water, and energy planning embedded in U.S. technical assistance programs never materialized. This left Afghanistan with no coordinated mineral-energy strategy, even as donors emphasized the role of these resources in national revenue generation and regional integration.

Between 2009 and 2021, U.S. agencies alone invested nearly $1 billion into Afghanistan’s extractives sector. Programs like the Extractive Technical Assistance (ETA) and the Mining Investment and Development for Afghan Sustainability (MIDAS) aimed to modernize licensing, improve institutional capacity, promote artisanal mining formalization, and support investment promotion. But as Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR’s) 2023 audit concluded, four out of five major components failed, with no lasting improvement in governance or sector performance.

The only partially successful outcome was the remote mapping of artisanal mining zones. All other reforms including the creation of a mining regulator, implementation of environmental safeguards, and establishment of fiscal monitoring tools were either abandoned or never enforced. These failures were intensified by donor reluctance to monitor outcomes, reliance on external contractors, and the absence of a coherent exit strategy as U.S. forces withdrew.

Since the U.S. withdrawal in August 2021 and the Taliban's subsequent return to power, they have awarded over 200 mining contracts to more than 150 companies, involving foreign partners from China, Iran, Turkey, Qatar, and the UK. In September 2023, the Taliban announced mining deals worth over $6.5 billion (Hunter & Ginn, 2025).

Despite its failure to capitalize on its resource base, Afghanistan remains strategically relevant. It lies at the center of multiple resource corridors, between China and Iran, and between Central Asia and South Asia. Chinese, Iranian, and Pakistani firms have all shown interest in copper and lithium assets, often pursuing bilateral arrangements outside Western oversight. However, unless a basic level of institutional legitimacy and investor protection is restored, Afghanistan will not integrate in the international minerals value chain.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan holds one of the most diversified mineral portfolios in the Eurasian region. It is a top global producer of uranium, chromium, lead, and zinc, with additional scale in copper, bauxite, iron, rare earth elements (REEs), and developing lithium reserves. Its vast, but like Afghanistan, landlocked geography neighboring Russia, China, and the Caspian Sea makes it a potential corridor for critical mineral flows tied to both Belt and Road infrastructure and EU diversification efforts.

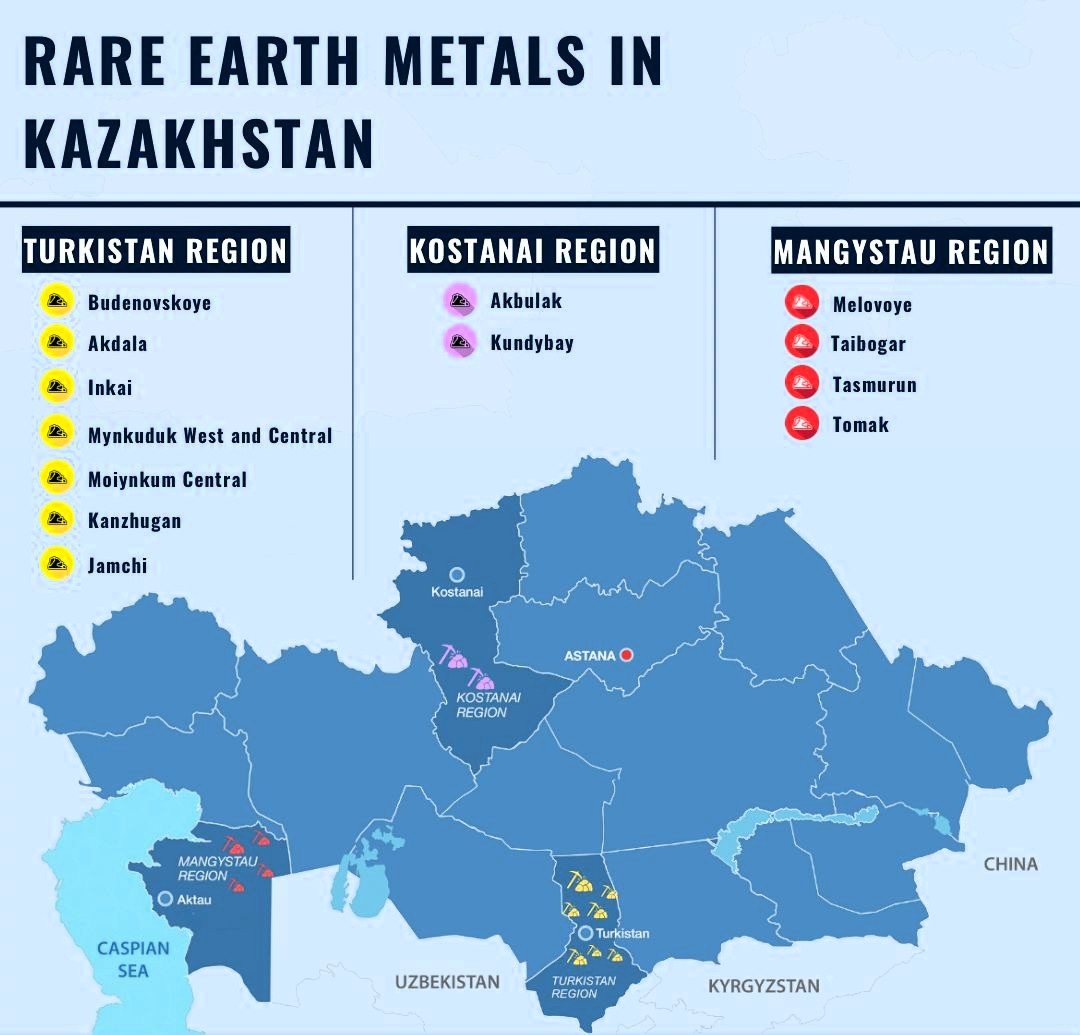

In recent public statements, Kazakhstan has begun to frame its rare earth elements as a national strategic priority, with President Tokayev describing them as “the new oil.” The country holds at least 15 known REE deposits across Turkistan, Kostanai, and Mangystau, yet these resources have seen little industrial development after decades of stagnation. To reposition itself in global supply chains, Kazakhstan has signed raw materials cooperation agreements with the EU, Germany, and South Korea, aiming to present itself as a non-Chinese alternative for critical inputs used in magnets, batteries, and hydrogen systems. However, domestic barriers such as limited processing capacity and partially digitized geodata remain unresolved. Experts continue to call for the establishment of a dedicated Ministry of Geology and the removal of speculative investors. As demand for REEs accelerates, Kazakhstan’s success will depend less on its resource base than on its ability to align national policy, institutional execution, and international credibility.

In 2018, Kazakhstan undertook a major overhaul of its extractive sector. The introduction of the Subsoil and Subsoil Use (SSU) Code replaced a Soviet-style concession system with a Western Australia–inspired first-come, first-served licensing regime. This code aligned Kazakhstan with international standards such as CRIRSCO reporting, digitized cadastre access, and simplified investor entry points. International observers, including the OECD and World Bank, initially hailed this as a turning point and a long-overdue modernization for a mineral-rich economy long dominated by state-owned interests, but after a few years, the progress has not been as expected. The new legal architecture has not led to a surge in significant exploration or downstream industrialization. Instead, the system remains dominated by state-owned enterprises, notably Tau-Ken Samruk, Kazatomprom, and Qazgeology, which continue to operate with privileged access to licenses and opaque accountability to the public. Institutional fragmentation persists, with responsibilities split across the Ministry of Industry and Infrastructure Development (MIID), the Ministry of Energy (for environmental coordination), and local Akimats (for permitting and land use). Regulatory procedures remain formally open but procedurally rigid as every operational change still requires state approval, and risk-based permitting remains elusive.

This disconnect is pronounced in the gap between Kazakhstan’s resource base and its energy transition positioning. The country is the world’s top uranium supplier and sits on industrial-scale reserves of copper, zinc, and manganese (all critical to battery storage, solar panels, and hydrogen production catalysts), but its mining sector remains locked into export of unprocessed materials. In 2023, more than 85% of mineral exports left the country as concentrates or raw ore, with very limited domestic refining or alloy production capacity. While copper, lead, and zinc dominate current exports, the latent potential in lithium, REEs, and nickel remains underdeveloped, both in infrastructure and investor interest.

The 2022 National Academy of Sciences strategic bulletin paints a candid picture. While the country has moved toward open data and public-private dialogue, it still lacks a coherent innovation agenda for subsoil use. Research funding is thin, environmental planning remains reactive, and industrial upgrading depends more on bilateral partnerships (with Germany and Korea) than on domestic capacity-building. The OECD notes that while legal harmonization has occurred, the real bottleneck is political economy as a risk-averse bureaucracy, crowding out of private actors, and limited enforcement of environmental or community development mandates.

To foreign investors, Kazakhstan presents a paradox with massive mineral geology without procedural efficiency, and its role in future supply chains will depend less on its mineral base and more on its ability to build transparent institutions and de-risk private investment.

Argentina

Argentina is often regarded as the most investment-accessible member of the Lithium Triangle. Its geological endowment goes beyond brines, including large undeveloped copper districts, significant gold and silver deposits, and early-stage exploration for nickel, cobalt, and rare earth elements. Its mining policy framework, while lacking a single integrated industrial strategy, offers long-term fiscal predictability, strong legal tenure, and investor-friendly licensing which is a rare combination among resource-rich developing economies.

But these institutional strengths are sharply constrained by Argentina’s federal structure, macroeconomic volatility, and geopolitical ambivalence. Provinces control subsoil resources and exercise licensing authority independently of the national government. National policy can enable, but not compel, provincial participation in strategic initiatives. As a result, Argentina’s mining landscape is a patchwork of investment climates, legal practices, and environmental enforcement regimes.

This fragmentation has not deterred foreign capital though because exploration investment surged by 77% from 2021 to 2023, reaching 427 million USD. Argentina ranked third globally in lithium exploration and eighth in copper, drawing attention from Chinese, U.S., and European firms. The appeal is in its stable concession law because the mining rights confer full ownership of the mineral deposit, and are indefinitely renewable, and freely transferable without state consent. The national Mining Investment Law guarantees 30 years of fiscal stability, and the 2024 “Régimen de Incentivo para Grandes Inversiones” (RIGI) offers up to 40 years of tax and currency protection for projects above $1 billion.

One thing to note is that Argentina’s currency regime is notoriously unstable and the peso lost 75% of its value year-over-year, and capital controls frequently prevent profit repatriation. Export taxes have been introduced, repealed, and reintroduced within single political cycles. Even as the mining legal regime remains unchanged, Argentina’s regulatory churn and macroeconomic distortion impose hidden costs that many Western firms find difficult to hedge.

There is a geopolitical dimension to the development of Argentina’s mineral resources. While Argentina is eager to position itself as a critical mineral supplier to the U.S. and EU, it is currently disqualified from many IRA-linked value chains due to Chinese ownership. Ganfeng and Zijin together control significant stakes in lithium production in Jujuy and Catamarca. Without ownership diversification, Argentine lithium will not be eligible for U.S. EV tax credits under Section 30D of the Inflation Reduction Act after 2024.

Copper offers a more flexible model because the government identifies a half-dozen world-class copper projects (Josemaría, Taca Taca, MARA, Los Azules) at various stages of development. These have attracted interest from Glencore, First Quantum, Lundin, and others. The challenge is less about legal clarity than about infrastructure, provincial coordination, and long-term energy provisioning. Processing capacity is limited, rail and port connectivity in the Andes is sparse, and in lithium-producing provinces, local communities often contest water use and land access even when surface rights are legally subordinated to subsurface concessions.

To make real progress in Argentina’s mineral sector, strategic investors will need to move beyond conventional off-take and equity models and instead build around provincial realities. The most promising approach lies in joint ventures with provincial SOEs such as JEMSE in Jujuy or YMAD in Catamarca that are structured to de-risk land access, expedite permitting, and secure community engagement. Long-term infrastructure co-investment, especially in lithium processing, water-efficient extraction technologies, or copper logistics corridors, can unlock latent project value while embedding the investor in Argentina’s broader development narrative.

Afghanistan:

Kazakhstan:

Argentina:

Sources:

Tiess, G., Majumder, T., & Cameron, P. (Eds.). (2023). Encyclopedia of mineral and energy policy. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR 23-10-AR). (2023, January). Afghanistan’s Extractives Industry: U.S. Programs Did Not Achieve Their Goals and Afghanistan Did Not Realize Widespread Economic Benefits from Its Mineral Resources.

World Bank. (2022). Mining Sector Diagnostic: Afghanistan (MSD). http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099020110252243379

Hunter, M., & Ginn, P. (2025, January 8). Treasure hunt: Why is Afghanistan part of the great extractives race? Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/why-is-afghanistan-part-of-the-great-extractives-race/

OECD (2018), Reform of the Mining Sector in Kazakhstan: Investment, Sustainability, Competitiveness, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2a7555f0-en.

Satubaldina, A. (2024, January 19). Kazakhstan boasts 15 rare earth deposits, eyes for deeper exploration. The Astana Times.

National Academy of Sciences of Kazakhstan. (2022). Public Administration Priorities of Subsoil Use in Kazakhstan. Bulletin of NAS RK.

Center for Strategic Initiatives. (2024, June). Mining Industry of Kazakhstan: Export-Oriented Metals.

“Ostensson, Olle; Parsons, Bob; Dodd, Samantha. 2014. Comparative Study of the Mining Tax Regime for Mineral Exploitation in Kazakhstan. © http://hdl.handle.net/10986/21587 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.”

Secretaría de Minería de la Nación. (2024, September). Minería Argentina: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/mining_in_argentina_1.pdf

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). (2024, May). Leveraging Argentina’s Mineral Resources for Economic Growth. https://www.csis.org/analysis/leveraging-argentinas-mineral-resources-economic-growth